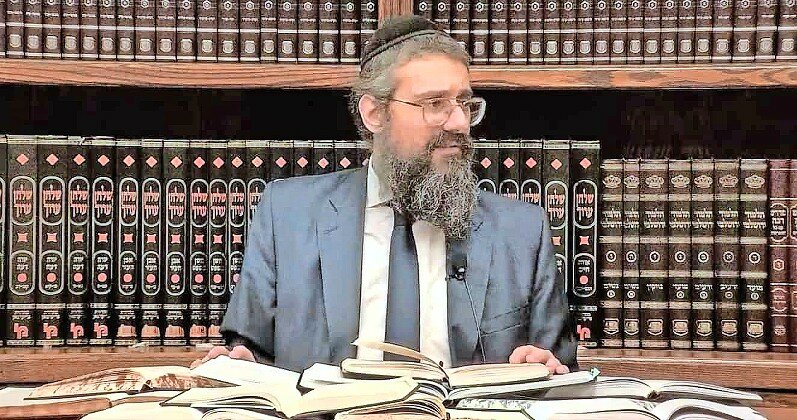

Toronto rabbi’s journey from shul to YouTube

Rabbi Mendel Kaplan still remembers the day in 2016 after morning prayers when congregants were talking about a woman, whose video of herself laughing while wearing a Chewbacca mask had gone viral on YouTube.

Kaplan, 52, religious leader of the 25-year-old Chabad Flamingo in Thornhill, a suburb in southern Ontario, Canada, figured that it was ridiculous for a clip of someone wearing a “Star Wars” accessory to garner so much attention.

“If people can watch narishkeit like this, maybe it’s a sign that I’m supposed to be doing something positive,” he told JNS he recalled thinking at the time. So he aired his first class on Facebook Live that afternoon — from the golf course, where the synagogue was hosting an annual charity fundraiser. As he streamed lectures live daily or even twice daily, he had no idea that someone was posting those videos to YouTube. When someone told him after three years that he had his own YouTube channel, he didn’t believe it.

“The whole thing was pretty wacky,” Kaplan told JNS. “Eventually, I reached the person who had been doing this.”

It turned out that the mystery person who was promoting Kaplan’s lectures was a former classmate of his when he studied at Central Yeshiva Tomchei Tmimim in Crown Heights neighborhood. The channel that Asher Furst had created was already drawing about 200 subscribers, and following a social-media campaign, it grew to 1,000 within 48 hours.

Nearly 7,500 people now subscribe to Kaplan’s YouTube channel, which has more than 1,400 videos that have been viewed nearly 650,000 times. His talks — topics range from Jewish history and Israel to the etrog, a ritual citrus fruit associated with the Sukkot holiday — can also be found on Spotify and Apple podcasts.

Kaplan told JNS that hears from people across the spectrum. Recently, for example, Pakistani, Indonesian and Iranian listeners have emailed him, and a Texas woman asked his advice on how to convert to Judaism.

“They ask questions about Judaism. People are interested,” he said. “They want to know about God. So, we are the light unto the nations. It’s part of our job.”

These are some of the many prominent figures who have spoken at Chabad Flamingo. And outside the public eye, Kaplan has a well-known Torah-study partner: the Jewish Canadian parliamentarian Melissa Lantsman, one of two deputy leaders of the federal Conservatives (opposition party).

Kaplan told JNS that he has led public menorah-lightings in Vaughan, a city in Ontario, during Chanukah for two decades. Last year, Lantsman approached him after the lighting and asked if he could spare the time to study Torah with her.

In the months since, the Chabad rabbi and Jewish parliamentarian have studied together daily in the morning (except Shabbat and holidays), wherever they happen to be in the world.

“It’s uplifting when people tell you they are spiritually growing from something you say,” Kaplan told JNS. He added that being able to teach the Torah is “the greatest gift you could ask for.”

The Talmud tells of someone who asked Shammai to convert him to Judaism while teaching him the entire Torah while standing on one foot. After the sage chased him away, the man asked the same of Hillel. The latter converted him and said: “Don’t do to others what is hateful to you. That is the whole Torah. The rest is commentary. Now go and study.”

Flamingos stand on one foot, but the synagogue, which takes its name from the street where it is situated — intersecting with Bathurst Street, a major road near where most Toronto’s Jews live along a roughly nine-mile stretch — stands on the contributions of several people.

Rabbi Zalman Grossbaum, Kaplan’s father-in-law, became regional director of the Chabad Lubavitch of Southern Ontario long before there was a substantial Jewish community in the area, let alone a synagogue.

The Jewish population was growing in the Toronto suburb of Thornhill, which now has Canada’s largest Jewish concentration — nearly 30% of residents, or about 35,000 Jews.

Grossbaum approached his friend Ernest Manson, a Holocaust survivor who ran the development company Emery Investments, with his vision for a synagogue. Manson, who died in 1990, agreed to donate the land for the new shul.

Since Manson’s passing, his wife Cathy and their children honored his pledge and transferred the property to Chabad of Ontario in 1998. As Grossbaum worked on creating a synagogue, Kaplan — taking after his father, Rabbi Nochem Kaplan, a renowned educator — began teaching in yeshivahs in St. Petersburg (Russia) and Buenos Aires (Argentina), as well as Los Angeles and Milwaukee.

He asked his father-in-law to take a chance on him and let him lead the new community.

“He was a little nervous at the beginning. He thought it wasn’t right to bring family into this. He thought people could see nepotism,” Kaplan acknowledged. “I made the argument that nepotism is when someone isn’t capable. I think we agreed I’m capable to do this.”

Kaplan started by reaching out individually to families. High Holiday services at Rosedale Heights Public School were his first big events. Thereafter, weekly services on Shabbat continued throughout the year in the Kaplans’ home.

By the High Holidays in 1999, Kaplan, then 27, held services in the congregation’s new 22,000 square-foot building — aptly named the Ernest Manson Lubavitch Centre.

The center contains a nursery school, synagogue, study halls, mikvahs, a library and a wedding hall. It all came together very quickly, according to Kaplan.

Today, the synagogue is typically packed for holiday parties on Purim, Sukkot, Chanukah and Simchat Torah. Programming geared towards a rising number of young professionals began 11 months ago, and a recent Friday-night dinner, led by Kaplan’s son Leibel and daughter-in-law Draiza, drew nearly 100 young professionals.

Being tethered is essential when one rubs elbows to the extent Kaplan does. In 2008, Chabad rabbis went to Parliament Hill in Ottawa. On the way out, Kaplan approached Stephen Harper, then Canadian prime minister, and asked him to deliver a talk from the bimah at the synagogue’s celebration of its expansion. Harper agreed, and in 2009, he addressed the congregants for 20 minutes.

Four years later, the community was inaugurating a new banquet hall — large enough to accommodate simchas, holiday parties and community gatherings. Kaplan hopes in the future to create affordable housing for couples on part of the parking lot — moving some parking below ground.

46.0°,

A Few Clouds

46.0°,

A Few Clouds