The Kosher Bookworm The Sepharad Siddur Brought Up To Date

Among the many new synagogues being established within our community today, it should be noted that the majority follow the prayer rite known as Nusach Sepharad. This rite has a long history, which was detailed by Dr. Philip Birnbaum, the pioneer American liturgist, in his introduction to his historic translation of the Sepharad rite close to a half-century ago.

Dr. Birnbaum stated the following:

“The Sephardic – Hassidic version of the prayer book, which was introduced by Rabbi Baal-Shemtov’s disciples in the 18th century, is in accordance with the arrangements and the additions of Rabbi Isaac Luria, the famous Kabbalist of the 16th century, known as the Ari. There have been no less than six versions of the so-called Siddur Nusach he-Ari, a fact sufficiently explaining why the Sephardic prayer books abound in variant readings, within parentheses, in the text. It is unfortunate indeed that, unlike the Ashkenazic editions of the prayer book, the Nusach Sepharad has never been edited by men like Heidenheim and Baer. Complete laxity and inconsistency on the part of printers and publishers are frequently to be found by the reader, who is confused and does not know what to say and what to omit.”

Birnbaum, in his edition, sought to correct these errors and to present a neat and accurate text of the Sepharad liturgy. His was the first major attempt to do so, together with a literate translation.

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, in his “Guide To Jewish Prayer,” observed concerning Nusach Sepharad: “As no complete Siddur with the exact version of Rabbi Isaac Luria’s prayer text has ever been produced, the numerous Siddurim bearing his name are actually based on the directives found in the book, Peri Etz Hayyim, and in several Siddurim containing orders of prayer based upon his special regulations and comments.

“Nusach Sepharad, which was created by superimposing Rabbi Luria’s instructions upon the Ashkenazic rite, is thus a hybrid, which is in some ways a mixture of the Ashkenazic and Sephardic [oriental] rites.”

Rabbi Steinsaltz notes some liturgical variances in the Sepharad nusach:

The recitation of Hodu before Baruch She’amar;

The addition of the phrase V’yatzmach purkanay in the Kaddish;

And, in the Kedusha of the morning service which begins with the phrase nakdishach, and in the Musaf Kedusha with keter.

Both the Birnbaum, and later, the Artscroll, edition attempted to establish a more uniform version of the Hebrew text, setting up their own respective versions of the variations that we inherited from previous editions. Further, the Artscroll commentary gave the liturgy its due, especially its notations concerning the Musaf Kedusha, something that has yet to be duplicated by others.

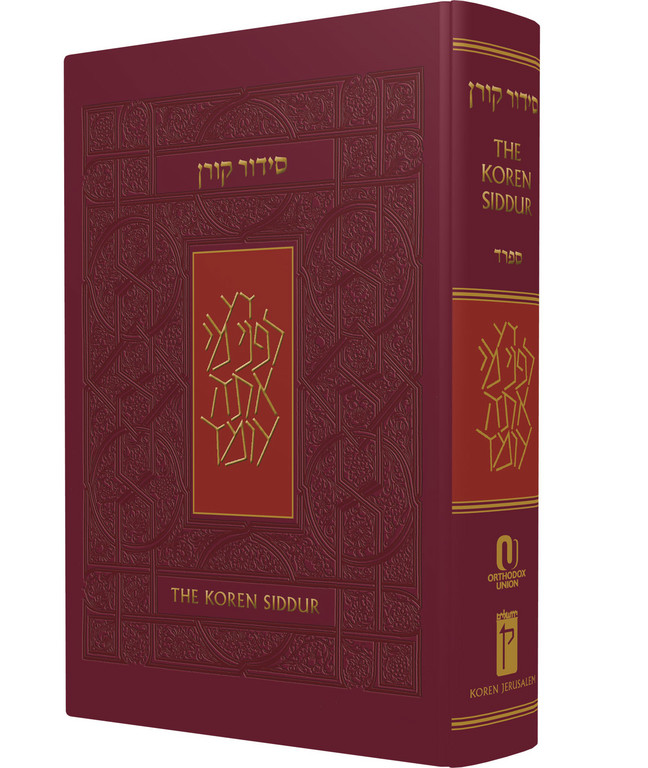

This past month we witnessed the publishing of a newly revised, corrected, and authoritative Hebrew text for Nusach Sepharad, with a new, more understandable, and accurate English translation and commentary by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. This new edition is based upon the original Koren Sepharad Hebrew text first published in 1981.

Similar in layout to the previous Ashkenazic edition, this newly revised Sepharad edition should prove to be an invaluable addition to the libraries of those shuls, as well as individuals who follow this nusach.

Also, as with the previous editions, the layout of the printed texts, as well as the instructions and directions, will prove to be an added boon to the worshipper, thus enhancing the ease with which he and she will pray utilizing this user friendly format.

FOR FURTHER STUDY

Several new books dealing with Jewish prayer have recently been published and each deserves your attention and patronage. First, we have “Laws of Prayer” by Rabbi Eliezer Melamed, Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Har Beracha. This work goes into great halachic detail in explaining the fundamentals of the laws of prayer, including the role of the chazzan, the proper place of prayer with chapters dealing, in great detail, with the content and purpose of the liturgical text of the siddur. This work is breathtaking in both its scope and detail.

Another work, “The How and Why of Jewish Prayer” by Israel Rubin also covers much of the same territory. However, the layman should find his treatment of the material to be a bit more user friendly, less technical, and easy to comprehend.

Lastly, we have “Prayer Works: How Words of Prayer Move the World,” by Rabbi Noson Weisz, the well known lecturer and writer for Aish HaTorah.

Rabbi Weisz, in his work, approaches prayer by analyzing its mechanistic nature and structure through the modeling of the Shema and the Shemoneh Esrei. His depth of analysis is enhanced by his eloquence of language that serves the reader well by keeping your interest despite its length.

All of these works will serve as valued supplemental readings to the new Koren Siddur. In all these works, the English is strikingly eloquent, sharp, and accurate in both detail and content. You will be well served by this new siddur, and you will surely find your prayers more meaningful for this.

43.0°,

Partly Cloudy

43.0°,

Partly Cloudy