Whether or not you are ‘visibly’ Jewish, they’re coming to get you

One evening about 30 years ago, my girlfriend, who is now my wife, returned to her small flat in London with her eyes swollen with tears, and the backs of her knees and thighs covered in painful bruises.

An hour earlier, she had been walking through Kings Cross train station when a young chassidic visitor to the city, lost in the web of the London Underground, approached her asking for directions. She duly took him to the correct platform for Heathrow Airport, picking up one of his suitcases along the way.

As she dropped him off and started walking back in the direction of her train, she heard footsteps behind her. Before she could turn around, she felt a series of brutal kicks to her legs. A voice hissed “You Jewish ----” in her ear as the kicks landed again.

Her assailant, a white male whose face she only glimpsed, ran off, leaving her terrified and dazed, while everyone around her carried on as if nothing had happened.

I have to admit I did a lousy job of comforting her. I was shocked and worried and angry, but I was also confused when she mentioned, with touching sweetness, her relief that the young chassid had been safely away from her when the attack occurred.

“Wait, what do you mean?” I blurted, as she sat down on the sofa with a cup of tea. “He attacked you because he thought you were Jewish, or because he saw you helping the chassidic kid?”

Exasperation flashed across her face. “What difference does it make?” she snapped.

My stupid question was a lesson in how I’d internalized anti-Semitic stereotypes more than I cared to admit. It dawned on me that I’d asked it because, with her blonde hair and blue eyes, my wife didn’t “look Jewish.” But to the lout who assaulted her, she was as much of a Jew as the young chassid she’d assisted — and she was, therefore, unambiguously the victim of an anti-Semitic attack.

Like many victims of anti-Semitic violence, she didn’t report the assault to the police, and neither did I, processing the incident instead as an ugly and painful memory. To this day, it still troubles me that my first reaction was to wonder why the assailant had identified my wife as a Jew.

If the assailant had spotted my wife helping the young chassid with his suitcase, then, to my mind, there was a rational explanation for why she’d been targeted. But what if the assailant had just decided on the spot that she was Jewish and therefore a legitimate target? That was too unpleasant to contemplate.On a purely empirical level, it’s a distinction that makes sense, insofar as hate-crime statistics show that “visible” Jews are more likely to face random violence than are “non-visibles” because, of course, they are identifiable as such by their clothing. But on a moral and political level, it is a distinction without value.

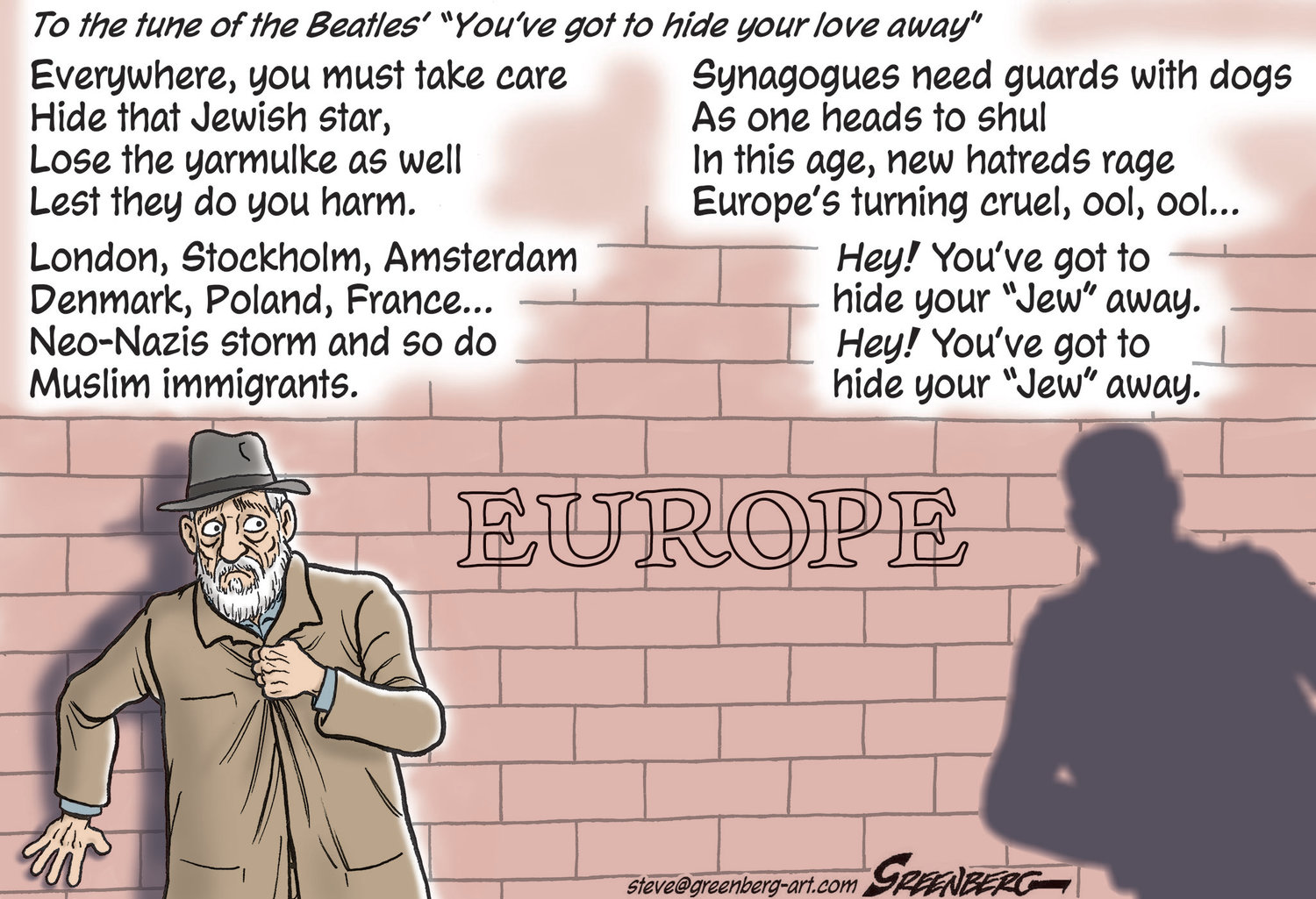

It reinforces, among both Jews and non-Jews, the notion that violence against visible Jews can be explained away; lunatics prowl the streets of our cities, and some of them are anti-Semites and racists with no self-control, so a Jew took a beating because he was unfortunate to be wearing a kippah in the wrong place at the wrong time. Next time, wear a baseball cap.

These generic platitudes are of little help in Crown Heights, home to the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, where in the last three months about a dozen Chassidic men have been brutally beaten up, leaving many in the community fearful, as one rabbi told me this week, of walking a couple of blocks to go to the store or visit a relative.

The most recent incidents took place within a few minutes of each other. Three African-American youths attacked a 22-year-old yeshiva student who was chatting on his cell phone, leaving him bloodied and disoriented on the sidewalk. Minutes later, the same youths attacked a 51-year-old chassidic man, dragging him to the ground as they kicked and punched him without mercy. Two have since been arrested by the NYPD and charged with hate crimes.

It’s a miracle, frankly, that none of the victims have been killed, but if the trend is allowed to continue, that can easily change.

Since the anti-Semitic riots of August 1991 in Crown Heights, there has been real progress in relations between the Orthodox Jews and African-Americans who live in the neighborhood side by side. And yet there is clearly a counter-process at work, expressed in the kind of violent and delinquent anti-Semitism that has become horribly familiar to French Jews living in poor neighborhoods of Paris alongside much larger Muslim immigrant communities.

Jewish community leaders in Crown Heights are right, therefore, when they insist on a proper investigation by city authorities into the circumstances underlying the current spate of anti-Semitic violence. To casually invoke “historical grievances,” the Black Lives Matter movement, or any other convenient filter as the sole reason for these attacks doesn’t help anyone.

Similarly, that the Crown Heights situation is an exception, not the rule, for most American Jews shouldn’t lead us to complacency.

Violence against “visible” Jews is an expression of hatred towards all Jews. True, the “non-visibles” among us are not on the frontlines — at least, not when we are casually walking the streets of our cities — but that is no reason for us to pretend that what’s happening in Crown Heights is not our problem.

Make no mistake: The fundamental impulse behind these assaults is the same impulse behind the Oct. 27 mass shooting of 11 men and women who became visibly Jewish as soon as they entered Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue.

54.0°,

Mostly Cloudy

54.0°,

Mostly Cloudy