Soros is despised by anti-Semites, political foes … and many Jews

Josh Kantrow is not a fan of George Soros, the Jewish billionaire financier and philanthropist.

Kantrow, 55, a Jewish lawyer and longtime Republican in Chicago, doesn’t like Soros’ long and expansive record of philanthropy toward progressive causes, including Democratic politicians. He doesn’t like Soros’ criticism of Israel and his funding of left-wing organizations there.

But Kantrow feels he needs to be careful when he criticizes Soros, who is a Holocaust survivor. He is OK with opposing Soros’ activities, but recognizes there’s a whole other type of Soros criticism — false and anti-Semitic — that he wants no part of.

“I talk about him very carefully,” Kantrow said. “To make clear that I’m disagreeing with him on policy. It shouldn’t have anything to do with his religion. And I wish everyone would do it like that and stop it with, like, ‘He’s the most evil man in the world because he believes this’.”

Kantrow is grappling with a question that his fellow Jewish conservatives have faced for years: What do you do when a leading progressive megadonor is also the most prominent avatar of contemporary anti-Semitism?

Conspiracy theories about Soros have long existed, but they gathered steam during Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis. Soros’ charity network, the Open Society Foundations, donates to groups that helped waves of migrants who sought to enter Europe, and anti-Semites have accused Soros of attempting to replace Europe’s white inhabitants with Muslim refugees. He has been a target of Hungary’s right-wing nationalist prime minister, Viktor Orban, who ran a billboard campaign against Soros that was denounced as anti-Semitic.

(The political consultants who recommended that Orban focus his criticism on Soros were American Jewish campaign strategists Arthur Finkelstein and George Birnbaum. Finkelstein died in 2017. Birnbaum did not respond to a request for comment.)

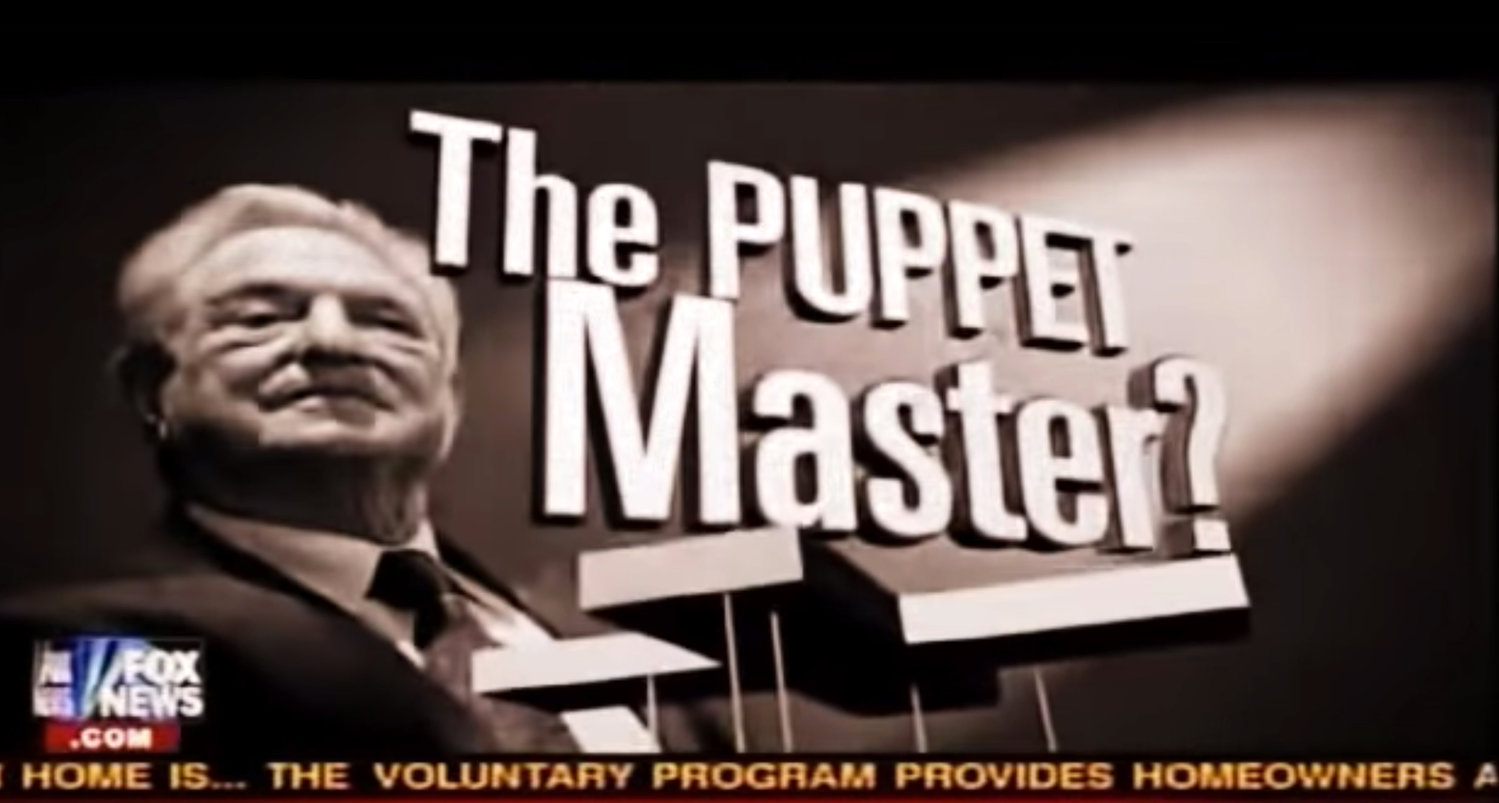

More recent, Soros has become a favorite target of far-right activists in the United States, who claim without evidence that he pays left-wing protesters or seeks to bring down the government. In 2018, a right-wing extremist sent a pipe bomb to Soros’ house. Days later, a man who had demonized him on social media entered a synagogue in Pittsburgh and killed 11 Jews.

• • •

In the past couple of years, Soros has been denounced on Twitter and elsewhere by President Donald Trump and many of his allies, including Rudy Giuliani and Rep. Kevin McCarthy. Recently, Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican congressional nominee in a solidly red Georgia district who has repeatedly called Soros the “enemy of the people” and shared anti-Semitic content online, was present at the White House when Trump accepted the official nomination to run for reelection.

This spring, there were half a million negative tweets about Soros in one day, according to the Anti-Defamation League, which says the Soros theories “can serve as a gateway to the antisemitic subculture that blames Jews” for unrest in the US. Many of the tweets, according to the ADL, blamed Soros for fomenting violence in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests.

This all creates a dilemma for Jews who oppose Soros’ actual activism but feel uneasy about the anti-Semitism against him. If you believe Soros is fundamentally opposed to what you believe are Jewish interests, such as support for Israel, what do you do when he’s the victim of Jew-hatred?

“Anti-Semitism works by inversion. It works by lying. It works by conflating,” said Ruth Wisse, an emeritus professor of Yiddish literature at Harvard University and conservative writer. “And it’s so difficult to pull some of the threads apart. This is one of the most difficult situations one can be in: when you have a Jewish anti-Jew who is attacked by anti-Semites.”

Jewish people who wield influence, like Soros, shouldn’t be immune from criticism by virtue of their Jewishness, said Josh Pasek, a University of Michigan professor who studies new media and political communication. But Soros’ status as a target of anti-Semitism, he said, means that Soros critics should know their comments will likely be used by those who hate Jews, especially in a climate where conspiracy theories spread quickly on social media.

This is true as well, Pasek said, when those on the left criticize Jewish neoconservatives who support Israeli policy.

Some Jews on the right feel no compunction about Soros bashing, regardless of the anti-Semitism directed at him. Some insist that the conspiracy theories about Soros are not anti-Semitic or are a minor issue when compared with the damage they believe his philanthropy causes.

Yair Netanyahu, the son of the Israeli prime minister who’s known for spreading falsehoods and conspiracy theories on social media, posted a meme on Facebook in 2017 showing Soros dangling the globe on a string in front of a reptilian creature. The meme also included a classic anti-Semitic caricature with a hooked nose.

Netanyahu deleted the meme following a broad backlash, but has since publicly criticized Soros multiple times. Last year, he accused Soros of “destroying Israel from the inside,” and tweeted that “Soros is the number 1 anti Israeli and anti Jewish world actor.”

• • •

There are, likewise, Jews who make a point of defending critics of Soros from charges of anti-Semitism. The Coalition for Jewish Values, a right-wing Orthodox group that claims to represents a number of rabbis, has released statements defending both Giuliani, the former New York mayor and now Trump’s personal attorney, and McCarthy, the House Republican leader, from such charges.

In October 2018, McCarthy had tweeted, then deleted, that “we cannot allow Soros, Steyer, and Bloomberg to BUY this election!” referencing three Democratic donors who are Jewish or of Jewish descent. He denied the tweet was anti-Semitic. In a statement, his office said the tweet was deleted because of “the political climate today that has led to specific threats,” presumably referring to the pipe bomb attack on Soros, which had occurred one day before the tweet was posted.

Last December, Giuliani said that he was “more of a Jew than Soros is” and falsely accused Soros of employing FBI agents and controlling a U.S. ambassador. The rabbinic group’s president, Rabbi Pesach Lerner, called Giuliani’s statements “entirely reasonable.”

“Yes, Soros is part of the Jewish nation, but ideologically he is not merely distant but openly hostile towards Israel and Jewish interests,” Lerner said in a statement at the time. “It is ridiculous to link an accurate critique of the use of Soros’ wealth to influence certain public officials to hateful, anti-Semitic lies about Jewish communal control over government at large.”

Like some other Jewish conservatives, Lerner questions the claim that Soros is a frequent victim of anti-Semitism, and defends those who are accused of bigotry against Soros, because he believes Soros is only superficially Jewish. He does not feel Soros leads a Jewish life and says Soros works against the Jewish people. He likewise thinks that Soros’ funding activities are more dangerous than any anti-Semitic invective directed toward Soros.

“He is not part of the global Jewish community, other than being Jewish by birth,” Lerner told the JTA last month. He added later, “One must be aware and sensitive to anti-Semitic tropes in terms of how to express the criticism. But the damage done by Soros is so great that silence is by far the greater danger — and valid criticism can rebut the notion that he in any way represents ‘the Jews’.”

Rabbi Steven Pruzansky, a vice president of the Coalition for Jewish Values with a record of inflammatory statements — including one belittling allegations of campus rape and another saying Arab Israelis and Palestinians “must be vanquished” — wrote to JTA that Soros has “a long history of anti-American, anti-Israel and anti-Jewish acts.” He added, “Trying to inoculate him from justly earned criticism by playing the ‘anti-Semitism’ card is one of the great charades of our age.”

• • •

Emily Tamkin, author of “The Influence of Soros,” a recent book about Soros’ philanthropy and the conspiracy theories targeting him, said attitudes like Lerner’s go a long way toward explaining how Jews can find themselves attacking the same man who has faced a torrent of anti-Semitism in recent years.

“I think it comes down to your understanding of Jewishness and what it means to be Jewish,” she said. “Soros has funded groups that work to promote Palestinian rights. If you think that being Jewish is first and foremost being concerned with Israel and with an Israel that gets to do what it wants, then Soros is against your understanding of Jewishness.”

Tamkin said that sheds light on criticism of Soros from pro-Israel figures, including Yair Netayahu and his father, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose Foreign Ministry released a statement in 2017 saying Soros “continuously undermines Israel’s democratically elected governments.”

The younger Netanyahu is not the only right-wing pro-Israel figure to traffic in Soros conspiracy theories. Adam Milstein, a prominent right-wing pro-Israel donor who has claimed that Soros funds antifa, the loose anti-fascist network, has called him a self-hating Jew and even questioned his background as a Holocaust survivor. In 2017, Milstein tweeted, then deleted, an image of Soros as an octopus with his tentacles around the globe (octopuses or tentacled monsters have been a common element in anti-Semitic imagery, including that of the Nazis). Milstein declined a JTA request for comment.

Morton Klein, president of the right-wing Zionist Organization of America, has compared Soros to the former head of the Ku Klux Klan, tweeting, “Condemning anti Israel extremist George Soros is not antisemitic just like condemning racist David Duke is not anti White.”

Klein isn’t worried about providing fodder for anti-Semites because he does not believe Soros is a target of anti-Semitism. He repeatedly told JTA that he has no problem with a cartoon showing Soros as an octopus controlling the world, for example, because he said Soros “has his tentacles all over the place and has enormous influence.” Klein acknowledged that such an image could echo an anti-Semitic stereotype about Jews, money and power, but said that in Soros’ case it is warranted.

“I myself would do a cartoon, if I was an artist, showing him controlling the world,” Klein said. “Show me where he’s been a target of anti-Semitism and I will immediately consider it. I am not personally aware of where people have attacked him because he’s a Jew, no.”

(Asked whether he would make the same determination about a cartoon depicting Republican Jewish megadonor Sheldon Adelson controlling the world, Klein said that while Soros funds “all sorts of influential groups that impact all of us around the world, Sheldon is really not quite as extensive in his philanthropy,” though he added that such a cartoon about Adelson “wouldn’t necessarily be anti-Semitic.”)

• • •

Substantive opposition to Soros’ views and activism is far from rare in centrist and right-wing Jewish circles, mostly centered on his critical attitudes toward Israeli policy. Soros’ network of charities, the Open Society Foundations, has provided funding to several left-wing Israeli human rights groups.

Soros sparked a backlash in 2003 when he told a Jewish audience that “the policies of the Bush administration and the [Ariel] Sharon administration [in Israel] contribute to” a resurgence of anti-Semitism in Europe.

In 2007, he wrote a lengthy essay criticizing the “pervasive influence of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee,” charging the pro-Israel lobby with being “closely allied with the neocons” and “an enthusiastic supporter of the invasion of Iraq.” The essay claimed that AIPAC’s behavior lent “some credence” to the false anti-Semitic belief in an “all-powerful Zionist conspiracy.”

“I am not a Zionist, nor am I am a practicing Jew,” Soros also wrote, “but I have a great deal of sympathy for my fellow Jews and a deep concern for the survival of Israel.”

The following year, he provided $245,000 in funding for J Street, a new left-wing Israel lobby and rival to AIPAC whose launch was greeted with suspicion among establishment Jewish organizations. By that point, Soros’ presence was so contentious in Jewish political circles that J Street concealed his involvement at his request. The donation and subsequent ones were uncovered in 2010 by The Washington Times, a right-leaning publication.

“It was his view that the attacks against him from certain parts of the community would undercut support for us,” J Street President Jeremy Ben-Ami told JTA at the time. “He was concerned that his involvement would be used by others to attack the effort.”

One of the Jewish leaders who condemned Soros after the 2003 speech was Abraham Foxman, the former head of the ADL who, at the time, was seen as an arbiter of anti-Semitism. He said that Soros, in linking the Sharon government to anti-Semitism, was “blaming the victim for all of Israel’s and the Jewish people’s ills.”

Nearly 17 years later, Foxman said, his thinking has changed as anti-Semitism against Soros has spiked. He still disagrees with Soros’ views, but said that Jews across the board — even those who vehemently oppose Soros — need to speak out against the anti-Semitism he faces.

“Today, it’s a shorthand: All you have to do is say ‘Soros,’ and it conjures up all of these anti-Semitic stereotype images,” he said. “They’ve succeeded in making him this icon, and therefore we have more of a responsibility to stand up to defend him because that’s not what he is.”

Pasek said that beyond grounding their criticism of Soros in specific examples, Jewish conservatives should consider taking it a step further and criticize the actions rather than focusing on the person. Conspiracy theories are so common, the Michigan professor said, that they could be fueled by any personal criticism of Soros, no matter the original intent.

“They need to tread very carefully,” said Pasek, who served as the chair of the Young Democrats of America Jewish caucus more than a decade ago before moving into academia. Critics’ focus on Soros, he said, “invites a whole bunch of things that will, in practice, provoke anti-Semitism. And I don’t think that means there isn’t a basis for criticism, but I think the basis needs to be substantive and needs to not focus on Soros.”

Kantrow, the Chicago-based lawyer and occasional political commentator, feels that there’s “a pretty stark line” between legitimate and illegitimate criticism of Soros. But often, he said, he feels uncomfortable with the rhetoric coming from others on the right.

“I see Soros as really aligned against the issues and things that I care about,” he said. “It doesn’t mean that he should be called some of the names that folks on the far right call him. I’ve seen him called a Nazi. That is disgusting. I’ve seen lots of things said about him that I would never, ever say.”

56.0°,

A Few Clouds

56.0°,

A Few Clouds